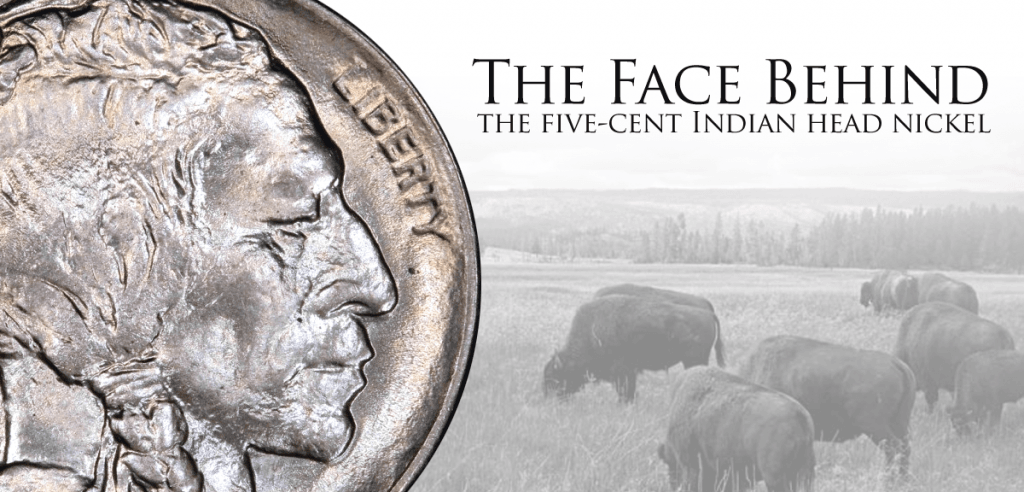

The Face Behind the Five-Cent Indian Head Nickel

The buffalo nickel is technically known as the “Five-Cent Indian Head” coin. It’s also commonly referred to as the “Buffalo Nickel” or “Bison Nickel” due to the bison on the back and often the “Indian Nickel” based on the portrait of a classic American native on the front. But have you ever wondered whose portrait decorates the coins front?

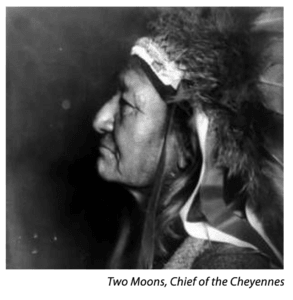

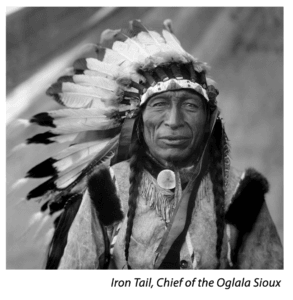

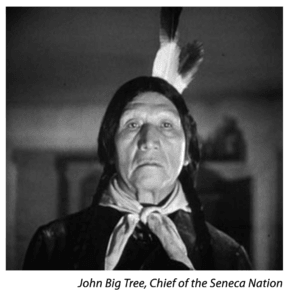

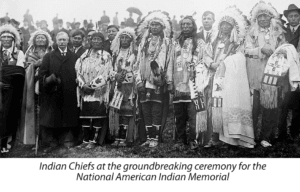

Surprising enough, the actual design on the coin’s front is not any one particular person. That’s right, Fraser used a combination of three Indian chiefs to create his unique design. Also, for his Indian head depiction, Fraser used living models, something virtually unheard of in an era when the classical profile from Greece or Rome was considered the highest ideal of art. Three different Indians, Iron Tail, Two Moons and though often debated, Chief John Big Tree sat for this famous composite likeness. The finished portrait possesses great character, and shows the rugged individuality of the American Indian.

So who were these Indian chiefs that modeled for Fraser?

It’s interesting to learn they were each famous in their own way. Although there is some debate about the third Indian chief, Fraser noted Two Moons and Iron Tail by name and could not accurately recall the third chief. Despite the controversy, Chief John Big Tree profusely claimed that he was actually the third model.

After his surrender, Two Moons chose to enlist as an Indian Scout for the same General to whom he had not long since surrendered. Because of Two Moons’ pleasant personality, the friendliness that he showed towards the whites as well as his ability to get along with the military, he was appointed head Chief of the Cheyenne Northern Reservation.

Due to his association with Wild Bill Cody and the Wild West Show, Iron Tail was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents.

Big Tree claimed to be one of three Native American chiefs whose profiles were composited to make the portrait featured on the obverse of the United States’ Indian Head Nickel and further claimed that his profile was used to create the portion of the portrait from the top of the forehead to the upper lip.

No matter who the third chief was, the compilation image for the obverse design depicts a large, powerful portrait of an Indian, facing right. The appearance is rough looking, unlike the smooth cheeks and other facial features that typify the many versions of Lady Liberty that have been on U.S Coins. We do know who the model was for the reverse side of the coin, and it is commonly mistaken for a buffalo, but is actually a bison on the reverse.

The Buffalo Nickel was officially introduced into circulation on March 4, 1913, and within a week Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber was expressing concern about how quickly the dies were wearing out during production. According to his estimates, Buffalo Nickel dies were wearing out and breaking more than three times faster than the Liberty Head Nickel dies. Barber and others at the Mint also believed the Buffalo Nickel wouldn’t hold up very well to ordinary wear and tear, and that in particular the date and the “FIVE CENTS” marking would wear away completely. To correct these problems, Barber prepared several revisions to the design, Fraser approved them, and this slightly revised Buffalo Nickel went into production right away. An interesting side note, Barber’s revised dies wore out even faster after his revisions, and the changes never did help with the wear problem.

One of the most interesting versions of the Indian head nickel is the 1937-D. The story goes that a worker at the Denver Mint polished a Buffalo Nickel die to remove “clash marks” — the marks and scratches that occur when dies are stored in direct contact with each other. Unfortunately, this worker did his job a little too thoroughly and not only removed all the clash marks, but one of the buffalo’s legs as well. Amazingly, this mistake was not caught until after thousands of these “three-legged nickels” had been minted and put into circulation.

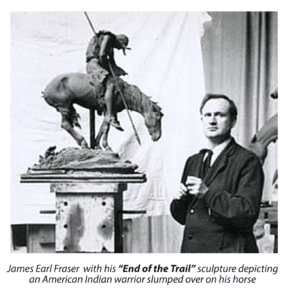

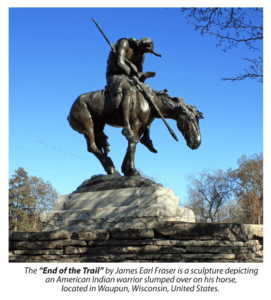

Tags: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Bison Nickel, Black Diamond, Buffalo Nickel, Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber, Chief John Big Tree, Coin History, End of the Trail, Iron Tail, James Earl Fraser, Jefferson nickel, Liberty Head Nickel, National American Indian Memorial, Thomas Jefferson, Three-Legged Buffalo, Two Moons, U.S. Coin History, U.S. Coins, United States Mint, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA